- News

- A High-Performance Handwriting BCI – 1st Place Winner of the BCI Award 2020

A High-Performance Handwriting BCI – 1st Place Winner of the BCI Award 2020

Francis R. Willett, Donald T. Avansino, Leigh Hochberg, Jaimie Henderson and Krishna V. Shenoy submitted their work to the BCI Award 2020 and won the 1st place! The team joined forces from Stanford University, the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Brown University, Harvard Medical School and the Massachusetts General Hospital to decode handwriting with a BCI. We had the chance to talk with Frank about his work.

You are currently viewing a placeholder content from Youtube. To access the actual content, click the button below. Please note that doing so will share data with third-party providers.

Hi Frank, you won 1st place of the international BCI Award 2020 competition. Could you briefly describe what this project was about?

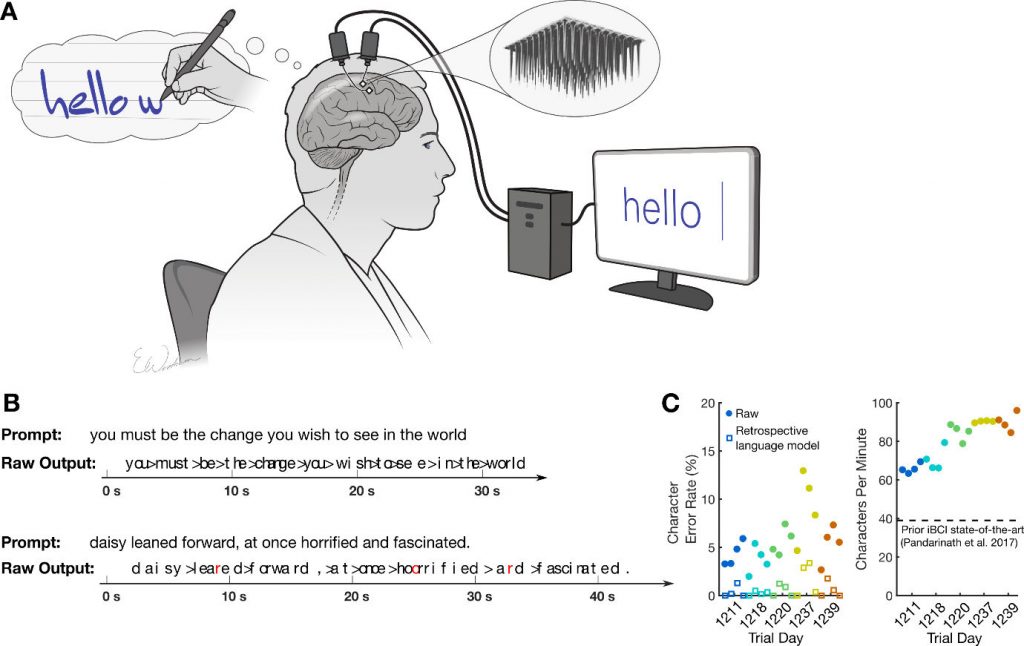

Frank: “Our project was about building an intracortical BCI to decode handwriting movements in a person with paralysis. This approach can enable someone who is locked-in to type text on a computer by attempting to handwrite it. We demonstrated our BCI in real-time in a person whose hand was paralyzed, and showed that it effectively doubled the prior record for BCI communication rate while achieving high accuracies.”

What was your goal?

Frank: “Our goal was to demonstrate the feasibility of decoding dexterous behaviors from a person with paralysis, with enough accuracy and speed to significantly improve upon the state of the art in communication BCIs. First, we had to assess whether dexterous handwriting movements could even be decoded at all in someone who has been paralyzed for many years, since to our knowledge no one has done this before. To our surprise, we found that when we asked our participant to attempt to handwrite single letters, they evoked strong and repeatable patterns of neural activity that encoded the pen movement. Our next goal was to see if we could decode complete handwritten sentences, thus allowing someone to communicate a message by attempting to handwrite it.”

What technologies did you use?

Frank: “We used intracortical microelectrode arrays combined with a variety of computational techniques to achieve high decoding accuracies on this challenging problem. The major challenge we faced was training decoders on data where no overt behavior was available, since our participant’s hand was paralyzed. We borrowed techniques from the automatic speech recognition field to solve this problem, using hidden Markov models to infer when our participant wrote each letter in the training data. After completing this inference step, we then used machine learning techniques to train recurrent neural networks to convert the neural activity into the probability of each letter being written at the current time. Finally, we used large-vocabulary, general-purpose language models to autocorrect for occasional decoding errors.”

What kind of people could benefit from your research?

Frank: “The people that would benefit most from this kind of research are those with severe paralysis or who are ‘locked-in’ and have no other means of rapid communication. One promising thing about this work is that it significantly increases the speed of BCI communication (to approximately 18 words per minute), making it more likely that someone could benefit from this technology even if they have some rudimentary, retained motion.”

Main Result. (A) System diagram. (B) Example sentences decoded in real-time (“>” denotes a space and errors are highlighted in red). The BCI is entirely self-paced and unconstrained (the user can write any sentence). (C) Typing accuracy (character error rate, left) and speed (characters per minute, right) over five days of evaluation. Each circle corresponds to a single “block” of 7-10 sentences.

Do you think your work as future potential for clinical use?

Frank: “Yes, we think that the high speed and accuracy that our BCI achieved on general-purpose sentence writing is promising for clinical viability. To our knowledge, this is the fastest communication BCI that is also accurate and general enough to enable the user to write any sentence. It is also entirely self-paced and leaves the eyes free to look anywhere. One remaining challenge, however, is the need to retrain the decoder each day to account for changes in the neural recordings that occur over time. We are currently working on methods to retrain the decoder in an unsupervised way in the background, so that the user does not have to be interrupted for retraining. This is still an outstanding challenge for BCIs in general, but it is encouraging that many groups are beginning to tackle this problem. I think it’s likely that a combination of algorithmic innovation on this front, combined with improvements to device stability, will continue to improve the robustness of intracortical BCIs.”

How was it to win the BCI Award 2020?

Frank: “It’s great to be recognized as doing useful and interesting research, and I’m thankful that the field has the BCI awards as a place to highlight and be inspired by the latest BCI developments.”

How can students, researchers get involved in such research?

Frank: “Our work is highly interdisciplinary, intersecting with hardware and device design, computational techniques from computer science and machine learning, and basic neuroscience. Students and researchers can contribute by working on the next generation of electrode technology, designing new algorithms for decoding neural activity, and expanding our knowledge of the brain circuits that underly the control of movement. In the intracortical BCI field, more labs are now getting involved in clinical trials, as we have done here. In addition, new companies are joining the field (e.g. Neuralink, Paradromics). The future looks bright for BCIs!”

Francis R. Willett1,2, Donald T. Avansino1, Leigh Hochberg3, Jaimie Henderson1, Krishna V. Shenoy1,2

1 Stanford University, USA

2 Howard Hughes Medical Institute, USA

3 Brown University, Harvard Medical School, Massachusetts General Hospital, USA